Ever since I started to investigate my paternal Skyvington genealogy, back in 1981, I've been obsessed by an obvious question:

Would I ever know the name and origins of the Norman knight—a companion of William the Conqueror—who might be thought of as the patriarch of our primordial Skeffington family in England?

Such an individual surely existed, and he had received the territory of the Saxon place called

Sceaftinga tûn—the

tûn (settlement) of

Sceaft’s people, to be known later on as the Leicestershire village of

Skeffington—as a reward for helping the Duke of Normandy to conqueror England.

But, in the list of names of the Norman knights who accompanied William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, I had no means of figuring out which one of them was our future patriarch. I often said to myself that, if only I knew the identity of "my" Norman knight, and if ever this individual happened to have descendants in France today, then these folk would be my "genetic cousins" (as they say in the domain of DNA-based genealogical research). I realized, however, that these were two big and unlikely if conditions...

The standard version of the story of the Skeffingtons was written in the 18th century by a plump English chap named

John Nichols.

Nichols was a prolific professional writer who succeeded in churning out a vast collection of historical tidbits about the county of Leicestershire. In this context, it was natural that he should devote numerous pages of his History and Antiquities of Leicestershire to a presentation of members of the distinguished Skeffington family. At no point, however, was Nichols capable of indicating explicitly the likely identity of our 11th-century patriarch.

Nichols did however mention the existence in 1231 (that's to say, 165 years after the Norman Conquest) of an individual named

Odo de Scevington, who owned lands down in Kent. Clutching at straws, I wondered if this individual might have descended from a celebrated personage with the same name: the Conqueror’s half-brother

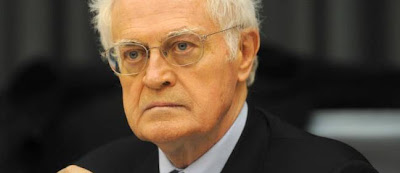

Odo, bishop of Bayeux, represented vividly in the famous tapestry.

It was ridiculous of me to speculate about links based upon no more than a shared given name. I had been momentarily enticed into imagining an association between the two Odo fellows because of another false reason, even more outlandish. Bishop Odo of Bayeux had a notorious habit, illustrated in the above image, of wielding a baton when he rode into battle. Now, the other Odo's surname, Scevington, evoked a Saxon warrior,

Sceaft (meaning shaft, spear or baton). I was mesmerized into imagining that the battle skills of the legendary Sceaft had been inherited magically by the Conqueror’s wild half-brother. Need I point out that my family-history thinking at that time had little in common with rocket science?

Two days ago (on Anzac Day), for the nth time in three decades, I happened to be skimming through the Nichols pages on the Skeffingtons, and my attention was caught by the presence of a reference to a late 13th-century individual, "

John lord of Verdun".

The term "Verdun" evokes, of course, the place on the Western Front in France where a horrendous battle took place in 1916, engaging the victorious forces of a certain

Philippe Pétain. Maybe those nasty evocations of 20th-century military butchery had dissuaded me previously from bothering to look more closely into the Nichols mention of this unknown "John lord of Verdun". On Anzac Day 2012, however, I made an effort, but the weight of all the World War I stuff meant that Google in English wasn't particularly helpful. So, I switched to French, replacing "John" by "Jean". And almost instantly, the facts concerning our patriarch started to unfold before my astonished eyes.

The name of our likely patriarch is

Bertram de Verdun. Today, his domain in the splendid countryside of Normandy has dwindled to a humble signpost on the outskirts of the town of Vessey. That should discourage any squabbles among us concerning rights to the family castle... if ever it existed.

The Verdun domain of our probable patriarch in Normandy is indicated by the red blob in the following Google map:

Chances are that Bertram's ghost got shook up a bit back at the time of the Normandy landings in June 1944, which took place not far away. After all, this was the splendid gateway into the eternal province of Normandy... or the eternal province of Brittany if you happen to be traveling in the opposite direction. The town of Vessey appears to lie alongside one of the rural roads I used to take—between Alençon and Dinan—back in my youthful days when I would ride my bike from Paris to Brittany and back.

The shield of Normandy is composed of a pair of golden lions (

passant, as specialists say, meaning that the lions are running) with blue tongues and claws, on a red background.

Now, I can hear my readers saying that this Norman shield looks remarkably like the familiar banner of the kingdom just across on the other side of the

Manche (the stretch of sea that folk on the other side persist in calling the

English Channel).

Yes, it sure does, and that's not just a coincidence. The myriad of present-day associations of all kinds between Normandy and England were the consequences of the actions of a group of French tourists, in 1066, with names such as Guillaume, Odo, Bertram, etc. (If you're interested in this subject of heraldic emblems, click

here to access an excellent Wikipedia article on the origins of various English coats of arms.) Even our respective languages reveal countless common features... which means that it's not really rocket science (I like that expression, don't I) when an English-speaking individual such as me gets around to communicating in French.

All the rumbling of canons on D-Day would not have alarmed unduly the ghost of an oldtimer such as Bertram de Verdun who had lived through the battle of Hastings, on the other side of the Channel.

After the Conquest, when things settled down a little in England, the Domesday Book reveals that our patriarch Bertram de Verdun was officially allocated enough earth to plant a vegetable garden on the conquered land (which happens to correspond exactly to my own activities at the moment of writing).

But what do we really know today about our patriarch Bertram de Verdun? Yesterday, following my discovery of this man, I was delighted to learn that a scholar at the Bangor University in Wales,

Mark Hagger, has published a book about the family de Verdun:

For the moment, for me, this whole affair is totally new. So I know little about our Norman patriarch. Click

here for an English-language Wikipedia article about the family, and

here for the French-language version.

Another fascinating question emerges. Is it thinkable that our patriarch Bertram de Verdun might have descendants today in France and elsewhere? Well, to put it mildly, judging from what I've seen through a rapid visit to the

Genea website, it would appear that the community of my so-called "genetic cousins" includes many present-day members of the old nobility of Normandy and France.

Les sanglots longs des violons

de l'automne blessent mon cœur

d'une langueur monotone.

[Click here to see why I ended this article with those splendid lines of poetry.]